Biography

Hans-Joachim Staude

A Life for Florence

by Angela Terzani Staude

1904-22: From Haiti to Hamburg. Growing up

Hans-Joachim Staude was born in 1904 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. It was a colonial world of exotic beauty as depicted in the novels of Pierre Loti. His father, Hans-Carl, came from an established German family of academics from Halle and had been lured to the island by his romantic dream of life in the tropics. There he lived as a businessman. His wife, Elsa Tippenhauer, had a German father and a Franco-Haitian mother and was herself born in Port-au-Prince.

-

Haiti 1905: Hans-Jo hold by his mother,

with the father and major brother

Hans-Jo, as he was called, spent his childhood in Haiti. While his father traded in the Caribbean, his mother read and played the piano with the ladies from the capital. The strong colours of flowers and fruits, the French chitchat of his aunts, and the distant view of mountains covered in dark jungle, resounding with the mysterious tom-tom of the Voodoo drums, remained forever engraved in Staude’s memory.

-

Port-au-Prince: Mother Elsa

on the veranda at home

In 1909, when Hans-Jo was five, Elsa moved with him and his elder brother to Hamburg to send them to school. Those were the last years of the German empire and the official culture was heavy with nationalist rhetoric. But the seeds of the ideas that would change the world had already been sown: Nietzsche’s philosophy, Freud’s psychoanalysis, Strindberg’s theatre, Schoenberg’s music, and the paintings of the young German expressionists.

The family bought a house in the Koernerstrasse, close to the Alster, the melancholy lake in the inner city, and settled into a bourgeois existence. Elsa, however, who herself had been educated in Hamburg and was therefore nicknamed by her brothers “la petite allemande”, soon ventured out to read some of the first “forbidden” volumes, joining the intellectual and artistic circles of the avant-garde. Soon she became a good friend of Rosa Schapire.

- The family’s house in Hamburg

When the First World War broke out, her husband was unable for several years to leave Haiti and spend the summers with his family, leaving Hans-Jo to grow up under the exclusive influence of this woman so passionately drawn to culture.

At thirteen, Staude jotted down the text of his life’s commitment in a notebook dedicated to “philosophical thoughts”, where this one remained the only entry: ‘Any human being must have a conception of the world: or at least anyone who has started to think a little! My conception of the world is the following […]: As much as I can, I want to contribute to the construction of the mighty edifice that the minds of earlier times have built and those of the present keep building; and I shall be satisfied to depart from life only if, looking back, I can honestly tell myself: “You have placed your spirit entirely at the service of the grand endeavour”‘ (1917).

A year later, after seeing the first big Edvard Munch exhibition in Hamburg, he began to draw. Fascinated by German expressionism, which by representing the ‘inner universe’ opened up entirely new horizons for painting, Staude joined Schmidt-Rottluff and his group that belonged to the expressionist movement “Die Brücke,” and was swept away by that feeling of a ‘departure towards new shores’ that gripped Germany after the lost war.

For the young Staude these were the times of his ‘mystical conversations at Bellevue,’ a fashionable part of Hamburg where some of his family and friends lived. There, together with friends such as Fritz Rougemont, Heino Elkan, Adolf Schneider, Kostek Gutschow and his cousin Olaf Oloffson, he pledged his life to the renewal of art and culture. Together with a class mate, Karl Broecker, he even produced a small magazine, “Die Werdenden” (Those who are becoming), in which they published their expressionist poems and wood-cuts.

At school he delved into the German classics. He wrote his Abitur (graduation) essay into which he introduced Friedrich Hölderlin, complaining that this poet, one of Germany’s greatest, was not being studied in the classroom. Reflecting upon Hölderlin’s life that had ended in madness, Staude wrote: ‘In him, the consistently recurring tragedy of the artist unfolds: the tragedy of the artist as he is perceived within our civilization after the Renaissance, i.e. after he seems to have lost his significance for society […]. Ever since then, we have grown accustomed to equating the great artists with the great sufferers.’ Staude also played the piano so well that it was generally assumed he would become a pianist. In 1920, at sixteen, Staude decided to become a painter.

-

Hans-Jo at the age of fourteen,

playing piano

In the following two years, he travelled widely to look at the great works of art of the past; and excursions to the lands along the River Elbe and to the Alps confronted him with nature, whose beauty and significance impressed him so much that in 1921, at Praxmar, a valley in the Austrian mountains, he promised himself that ‘as long as I shall see a tree, I will paint.’

Gradually, he distanced himself from Expressionism. ‘Before Expressionism the artist’s task was to represent nature,” he wrote to Adolf Schneider. “Ruysdael, Caspar David Friedrich and Manet sincerely painted the world as it was, or rather, as they sincerely saw it. Expressionism, on the contrary, does violence to the shapes of nature, preferring those ‘contemplated by the soul’; it emphasises what should remain unconscious, boasts about feelings.’

In 1922 Staude turned his back on Expressionism and began to observe nature. He wrote to his friend Gutschow, ‘To paint in front of nature is everything to me now.’

1923: Munich. The first teachers

The urge to paint all day long – ‘to finally become a worker!’ – dictated, from now on, all of Staude’s personal choices. He pursued his ‘visions’ and pushed ahead in what he defined as ‘my direction.’ Impatiently he awaited the end of school, yearning for ‘the South, where all art flourishes.’ His first stop-over was supposed to be in Munich where he hoped to study at the Academy of Fine Arts under Hugo Ernst Schnegg, an exponent of late German impressionism. In Munich, Fritz Rougemont was supposed to be waiting for him, ‘the understanding friend’ to whom he was drawn by a feeling ‘of belonging to the same time and the same intentions.’

But Munich turned out to be a disappointment. Schnegg was not there, Rougemont had left for Italy. ‘I must find myself,’ Staude wrote in his diary, awe-struck by the immensity of the task ahead. ‘I am fighting in these days a heavy battle […]. It is the battle for the new generation. For the new Germany, and for myself.’ Of his loneliness he wrote: “I am definitely fond of it now.” And of his painting: ‘The goal I can see; but the way – ah, if only I knew it!

1923-24: Haiti again. Light

In the autumn of 1923 Staude returned to Haiti, ‘the island where the first images impressed themselves upon my mind.’ He went to visit his father and stayed with him for six months.

With its magnificent vegetation, the remnants of 400 years of French colonization and the subsequent reign of the first black emperor, who had left it with huge castles, Haiti was considered the pearl of the colonies in the Western hemisphere. For Staude, its charm was heightened by his own family’s long involvement with the island’s history. His mother was descended from an uncle of Napoleon’s minister, Joseph Fouché, who at the beginning of the 19th century had taken refuge in Haiti and worked there as an architect; one of her brothers had built the harbour of Port-au-Prince; a sister had founded the legendary Oloffson Hotel.

‘Here we have sun, heat, brilliant light,’ he wrote upon revisiting the places of his early childhood. What seduced him, freeing him from his ‘ghosts,’ was life itself with its intensity of colours and beauty of gestures. He galopped on horseback through the exotic landscape, surrendering himself completely to it. ‘How can anyone who has never been South know about the senses!’ he wrote to his friend Heino Elkan. During the tropical nights he ‘sat with my bow tie on the lit verandah’ or attended dances and dinners, discovering his talent for the elegant life. Why not? he seemed to ask himself. Within a few months his handwriting acquired a confident new flow and curve.

In Haiti he also had his mystical moments. He spent New Year’s Eve on top of the barren slopes of Furey, alone with the mountain people and their voodoo. ‘If the soul had a birthplace, mine would be born here,’ he wrote his mother. Sometimes, in the bright sunshine, he felt pangs of nostalgia for the ‘gothic cathedrals,’ the ‘religious twilight of the Frauenkirche’ in Munich. He thought of Germany, of his friends, his interrupted work. He thought of Hamburg, ‘the lovely grey city on the Alster.’ In no trip, he said, ‘have I thought as intensely of home as during this one.’ He was, no doubt, a true European, rather than one of those who go adrift in the tropics.

1924-25: Hamburg

In the spring of 1924, after six months in Haiti, Staude sailed back to Hamburg. The ship berthed in Genoa. For the first time he set foot on Italian soil, but he did not want to stop, did not yet want to see that country.

Instead, he spent the summer in Finkenwerder, in the sombre northern German countryside as we know it from the paintings by Paula Modersohn-Becker and the Worpswede group. There he finally met with the painter Schnegg and promptly became his pupil. ‘Schnegg – a Bavarian, 48 years old – paints with blood and brush. Through him I learn what is learnable in painting. That’s quite a lot.’

He spent the winter in Hamburg, among people who were to leave a mark, in the homes of the avant-garde, among the city’s liveliest artistic and intellectual circles. He was a frequent guest of the Sudecks, in their home buried ‘in the bewitched gardens of Fonteney’, and the Warburg’s, the banking family. There, at a fancy dress party, he met Renate Moenckeberg, a young girl belonging to one of the city’s most cultivated and influential families. One day, she would become his wife.

But his painting did not satisfy him at all. Then, in the spring of 1925, he took off with Schnegg and a group of young painters on his first trip to Italy.

1925-28: Italy. Finding the landscape

Staude’s young years were ruled by a deep restlessness that kept him ‘in perpetual migration’. The young painter was searching for the landscape in which he could recognize himself, for ‘the landscape that I bear within me,’ as he wrote. He had ‘visions of pictures,’ but didn’t know how to translate them into paint. He had to find the picture outside himself, in the world, in nature. And he had to find a form for it, knowing well that ‘even that shall be provided by nature.’

But where was that nature, where was that landscape shaped like his visions?

He travelled, looked. He looked at the old masters, looked at the world. For many years he had studiously avoided Italy. The nostalgia for Italy lingers in every German who has read Goethe. Every painter has gone there and it seemed too obvious to Staude that he should have to go there, too.

And yet, once he arrived in Italy, Staude soon found himself in front of the very landscape he had been looking for. In Taormina began his growing disenchantment with the ‘bad impressionism’ of his teacher. Instead he began to organize his own paintings into masses of light and shade, ‘so that the anatomy of the painting may become clear.’ In Arezzo he saw the frescoes by Piero della Francesca and found them to be art in its highest expression of order, solidity and unity of colour. Now it was that his own pictorial intentions became clearer to him. In Florence, he decided to take leave of the group of painters he was travelling with and to stay on. In the broadest sense possible, he had found the landscape with the inherent order he had been looking for.

‘Florence. First of all it’s about the people,’ he wrote to Heino Elkan. To Kostek Gutschow: ‘And then, the countryside! […] Waves of hills, but they are constructed, shaped […].’ In Tuscany the sun shines upon people and things with inexorable precision, enabling the artist to carry through a study of nature that is simply impossible among the Northern mists. Not by chance, Staude found in Tuscany both the landscape he was longing for and his masters – Giotto, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca: for there seems to be an intimate connection between art and the landscape in which it was born. Now his own painting would be able to take shape.

During his first stay in Florence Staude led a simple life, in rented rooms (the first was in via Guicciardini) and at the studio with his models. Paul Winteler and his wife Maja, Albert Einstein’s sister, who lived in a farmhouse in the classical Tuscan countryside near Sesto – in an oasis they called ‘Samos’ – soon became his new family. The first Italian painter he met and whom he found a kindred spirit was Giovanni Colacicchi, who had just arrived in Florence from Anagni near Rome.

‘I find myself on a marvellous working path […] How I can ever want to leave this place I don’t yet know,’ he wrote to Gutschow in 1925.

-

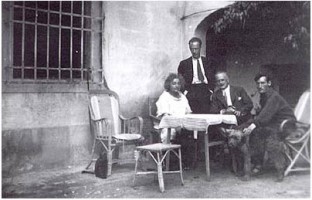

Staude (upright) with Maja Einstein Winteler, his uncle Georg Staude,

and Paul Winteler in Sesto Fiorentino

By no means had he given up his intention to participate in the renewal of the art of his time (‘We must be more than arabesques on the margin. We must be wheels that power the machinery of the world! Ah, if only that were possible again!’ he wrote in a letter of 1927 to Adolf Schneider). But he no longer spoke of working ‘for the new Germany.’ He was becoming more and more of a European, feeling committed to European art as a whole rather than to that of a particular country or people.

Between 1926 and 1928, in front of classical Italian art, he spelled out his own artistic convictions and established once and for all the guidelines along which he intended to proceed. His notebooks and letters of the time bear witness to an intellectual process which he would never again question.

As the years went by, Staude’s amazement at his adopted country never diminished. ‘The number of so-called ‘simple people’ who say things and have ‘ways of behaviour’ superior to ours, keeps increasing according to my experience,’ he wrote as an old man to the painter Odi Kasper. ‘That peculiar sort of spirituality that is sedimented in this landscape keeps surfacing in a conversation, a gesture.’

Yet, around mid-1928, after a severe nervous breakdown caused by the intensity with which he had worked, he began to doubt whether it wasn’t too easy, too obvious for him to be happy in Florence. And suddenly, taking a decision contrary to all his instincts, he put an end to his stay and returned to Hamburg.

1928: Hamburg. Interlude

In Hamburg he joined his old and lively group of friends again, which now included art historians such as Erwin Panofsky, Ernst Cassirer and Aby Warburg, the founder of the Warburg Institute (where Staude’s friend Fritz Rougemont was a fellow). Staude painted, was successful, sold his paintings easily, but Renate would remember him later as being highly-strung and restless at the time. In Hamburg he was seized by the fear that his abandonment of Florence had been a big mistake.

Besides, towards the end of the twenties the high hopes of the first postwar period began to decline in Germany. A sort of “Kulturpessimismus” began to surface among intellectuals, a depressed and negative attitude towards culture that Staude was in no way inclined to share. Profound differences were also arising between himself and his friend Fritz Rougemont, the one and only ‘understanding friend,’ differences that several years later transformed Rougemont into an ardent Nazi.

In 1929 the stock exchange crashed and his father went bankrupt. Staude was not much affected by it at first. With the money he had earned from selling his paintings in Hamburg he took off for Paris to study the newly discovered French impressionists.

1929: Paris. Finding new Masters

At the atelier “La Grande Chaumière,” where he was painting, Staude met the Austrian sculptor, Ludwig Kasper.

Kasper (1893-1945) was of farming stock. He was a man of few and grumpy words, but in the course of their visits to the Jeu-de-Paume, where the French impressionist paintings were hanging, Staude realized that this follower of the sculptor Adolf Hildebrand and the painter Hans von Marées had something fundamental to teach him, and he insisted that he should pass on to him some of his knowledge. In that situation which was so important for Staude, two works of art were created, of which regrettably only these photographs came to us through the years of the war:

-

The sculptor Ludwig Kasper, 1929

Oil on canvas

-

Ludwig Kasper: Portrait of

H.-J. Staude, 1929

Eventually, in front of the paintings by Cézanne and his contemporaries, Kasper spoke to him of the “concept of form,” a concept that defines the great art of all times and cultures and that now helped Staude to clarify and strengthen his own artistic intentions. ‘Nobody like Cezanne has mastered “trees”, “houses”, “faces” etc., turning them into the compositional elements of a painting,’ he wrote years later to his German friend Herbert Schmidt-Colinet. ‘He is the mother’s milk to us all.’

The break-up of the ‘motif’ into its elements of space, volumes, light and shade, and the composition of the painting according to formal and colouristic values derived exclusively from ‘the intrinsic law of the painting itself’ is Cézanne’s imperative, an imperative that lies at the heart of Staude’s art as well. To see today’s reality through the filter of ever-valid forms: that is what Paris had taught, and what Kasper had helped Staude understand.

During his stay in Paris, Staude saw Cézanne as well as Degas and Manet as his direct teachers, his forerunners. With them he would converse, to them he would compare himself, and this dialogue with the French impressionists continued throughout the years, till one of the last days of his life when, on being shown a watercolour by Manet, his eyes lit up: ‘Masterly – and so contemporary!’

Being ‘contemporary,’ being of its own time, was a value Staude highly appreciated in a work of art, which is why Paris, the city where modern art and literature were born, was to remain forever one of the havens of his nostalgias.

1929-40: Florence. The picture

Though ‘the way’ was now found, Staude remained restless, dissatisfied. But one day, during a short stay at Mont-de-Marsan, in the South of France, where he was resting at the home of a French cousin, Staude saw a fig tree through his open window. In front of the vision of that tree – which he must have likened to Italy itself – he recognized where his mistake lay. The very next day he packed his bags and left for Florence again, where he arrived on Whit Sunday. Sitting under the fig tree at Maja Winteler’s home, he wrote to Heino Elkan from the midst of the Tuscan campagna. This to him was ‘the landscape that I bear within me’ and he would never leave it again.

Of Germany he spoke little in the next decade. The friends from his younger years were going their own ways. His mind, however, was doubtlessly rooted in the German idealistic and romantic tradition, and with that spirit he settled down in Florence and began to paint.

After Paris and Kasper’s lessons, Florence became Staude’s touchstone. Having understood what stuff good painting was made of, he now had to prove himself. If during his first stay in Florence he had found his landscape, in the course of his second stay he settled down to painting. This took years of hard work.

First of all he put down his roots in the city. For a short time he lived at the Villa Romana, the home of German artists in Florence, to which also later he remained connected due to his deep artistic agreement with the new director, the painter Hans Purrmann.

But already in 1930 he found his definitive home at the Via delle Campora. The windows of the huge cinquecento-villa that had been built for Machiavelli’s niece, opened wide onto the Tuscan campagna. The peasants working in the fields became his models and, in the evenings, taught him the songs he would then sing to his guitar. ‘I should like to believe that this is the port I have reached after many wanderings. My “Port-au-Prince,”‘ he wrote to Heino Elkan.

- Villa Fossi in Via delle Campora, where Staude lived since 1930

Thanks to one of fortunate coincidences, which kept dotting his life, Staude even found a studio in the former convent of San Francesco di Paola, at the foot of the hill of Bellosguardo. Liesel Brewster, its owner, was the daughter of the German sculptor Adolf Hildebrand who in the 19th century had lived and worked there together with his friend, the painter Hans von Marées: precisely the two German artists to whom Staude felt indebted by way of Ludwig Kasper’s teachings.

‘Learning to see is everything,’ Hans von Marées had said, and throughout his life Staude tried to do precisely that, ‘only it takes so long before the eyes begin to really see!’ A journey to Spain in 1931, where he studied Velasquez, confirmed his artistic convictions.

Back in Florence, feeling the need to study the human figure, he joined the Academy of Fine Arts (1934 – 1937), drawing and painting nudes. The course was taught by the painter Felice Carena who was to become one of his closest Italian friends, as also the painters Giovanni Colacicchi, Emanuele Cavalli, Giorgio Settala, Filippo De Pisi, Toni Stadler, the art historian Friedrich Kriegbaum (who later became director of the German Institute for History of Art) and many others.

-

Staude (the first from left) at the painting class of the

Accademia delle Belle Arti in Florence

-

The Lady with the forelock, 1937

Oil on canvas, 92 x 68 cm

This painting was done in the Accademia

Florence, see above.

In the early Thirties, the news that reached him from home were distressing. Hitler came to power. Heino Elkan was forced to emigrate. Rougemont became a Nazi and their friendship came to an end. Staude’s father died and his mother moved to Florence to stay with him. Staude suffered another nervous break-down and from that time on insomnia remained a constant companion of his nights.

He discussed art less and less. He painted. ‘He who paints should never speak about art, much less should he want to make it. We must want to make nature. And if only because we are not God himself, art will result from it,’ he had written in his Munich diary. He continued, however, to jot down his thoughts about art and its related problems both in the little scrap books that he carried with him and in the letters he wrote to people of all kinds.

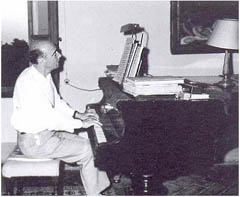

Music, of which in Munich he had written that ‘it has nothing to do with my visions: it is my way of dreaming,’ occupied an important place in his life. There was no evening when he wouldn’t sit down at the piano, playing or composing music. Before the war he studied composition with Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco; later he put to music a sonnet by Michelangelo and one by Lorenzo il Magnifico, a poem by Hoelderlin and one by Leopardi. He never ceased to mix with singers and musicians, and eventually resumed an old friendship with the dodecaphonic composer Luigi Dallapiccola. As Vittorio De Santis, a Florentine violinist friend, remembered, in music Staude gave free sway ‘to his romanticism that was both refined and intelligent, humane and mysterious,’ to that ‘lyricism’ which he had tried to bar from painting when settling down in Tuscany.

The new “understanding friend” became Christopher Norris, a young Englishman and art historian of exceptional talent whom Staude had met in front of a Velasquez painting at the Prado. Their friendship lasted a lifetime, but Norris remained indifferent to the ideal of creating a movement for the renewal of the art of their time that Staude was striving for. Though meeting many kinds of people, ultimately he remained alone.

In 1938 he married. Renate Moenckeberg, the young woman he had met in Hamburg in the winter of 1923 and who in the meantime had been working as an architect in Sweden, all the while visiting him in Italy each summer, fully understood his dedication to art. In Florence she continued to work as an architect, remaining by his side till the very end.

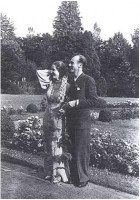

-

Wedding in Hamburg with the

architect Renate Moenckeberg.

In 1938, Staude also had his first one-man-show in Florence. It was a big success. He was thirty-three. One year later his daughter Angela was born and the pleasure of having a family overcame him. His family gave him support and joy, relieving the eternal solitude of the artist. His life was thus acquiring some of that “normality” for which, like a Tonio Kroeger, he had always yearned.

An exhibition of his paintings in Florence in 1940 and one in Rome in 1942, were both successful.

1940-45: Italy at War

In spite of Fascism, Florence enjoyed in the Thirties the most splendid times of the century. City and countryside were both at the height of their beauty, forming the backdrop to a social and cultural life that only the war would sweep away.

The great homes of Bernard Berenson or Charles and Olga Loeser, the villas of the Passiglis, the Franchettis, or the Brewsters, the palaces of the aristocracy and the upper bourgeoisie had among their guests many of Europe’s most renowned intellectuals and artists. With his charm and social talents, Hans-Jo, whose name had been changed to ‘Anzio’ by the Florentines, became part of that splendid world. In 1941, Marie Jose’, the Crown Prince’s consort and briefly Italy’s queen, took German lessons from him, becoming his friend and protector as well.

Frequently, he visited the German Institute for Art History, which under the prestigious direction of his friend, Friedrich Kriegbaum, was then at the height of its fame. In the thirties its ranks were filled by scholars and academics emigrating from Germany. Warmly received by the Italians at first, they further enriched the Florentine cultural climate with their talents. For a while Staude shared his flat with the art historian Wolfgang Paatz and the historian Nicolai Rubinstein who was to become the leading authority on the age of Lorenzo il Magnifico.

-

Friedrich Kriegbaum, 1932

Oil on wood, 61 x 50 cm

-

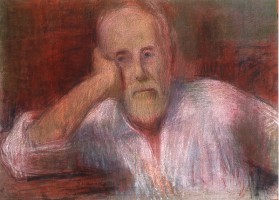

Felice Carena, 1960

Pastel on paper, 49 x 64 cm

-

Toni Stadler, 1966

Pastel on paper

He was a regular guest at the Villa Romana, a venerable institution accomodating German painters and sculptors. Staude remained always close to its new director, the painter Hans Purrmann, who had opened the Villa’s doors to the city’s artists and intellectuals. “Many times we went painting together”, Staude wrote, “and he remains the only painter to whom I feel tied by a sort of identity of vision as to what is ‘peinture’”.

The outbreak of the war depressed Staude deeply. To him the destruction of Europe – a cultural entity in which he profoundly believed – was equal to the destruction of one of humanity’s most precious heritages. He suffered from being German, from belonging to those who were using violence and speaking of nationalism whilst he so profoundly believed in the contrary, and did his best to work against that tendency (viz. the essays written by his German language students and the introduction with which he published them in a German magazine).

-

The airman first class of the Luftwaffe,

with his daughter Angela,

in front of his house.

He was a regular guest at the Villa Romana, a venerable institution accomodating German painters and sculptors. Staude remained always close to its new director, the painter Hans Purrmann, who had opened the Villa’s doors to the city’s artists and intellectuals. “Many times we went painting together”, Staude wrote, “and he remains the only painter to whom I feel tied by a sort of identity of vision as to what is ‘peinture'”.

The outbreak of the war depressed Staude deeply. To him the destruction of Europe – a cultural entity in which he profoundly believed – was equal to the destruction of one of humanity’s most precious heritages. He suffered from being German, from belonging to those who were using violence and speaking of nationalism whilst he so profoundly believed in the contrary, and did his best to work against that tendency (viz. the essays written by his German language students and the introduction with which he published them in a German magazine).

In 1942 he was conscripted into the German army and stationed as an interpreter in Italy. During the coming three years he stopped painting altogether. In 1943, after the Italian armistice, Renate had to move to Germany with their daughter Angela. During the war, Staude himself formed new friendships, both German and Italian that were to accompany him throughout the latter part of his life.

In 1945, during the German retreat, Staude was near Milan when he succeeded in slipping from the military convoy that was transporting him back to Germany. He cast off his uniform and, with the help of some Italian partisans, hid in civilian homes; then he surrendered to the Americans: it was unthinkable for him to leave Italy for good. After a few months as a prisoner-of-war he was able to return to Florence. Of that third arrival in the beloved city – where he found his mother miraculously unharmed and both his home and studio safe and intact – he wrote to his wife, saying that he had the impression that life had been bestowed upon him for a second time.

He resumed his painting at the point where it had been interrupted. But the cultural climate was changing so radically in Italy after the war that his “career,” which had started so successfully, was never to take off again. ‘Life has acquired something strangely temporary,’ he wrote in 1948 to Hans Kammeier, a musician friend from his Munich days. ‘All order and measure seem to be undermined. And the future approaches behind a hostile mask.’

1945-73: Florence. Painting

In this third and last stage of Staude’s life – which comprises almost thirty years of incessant work – tradition and the contemporary spirit, vision and technique moulded themselves into his painting.

After the war his art kept evolving. “The new religion: that of the loneliness of man”, of which Staude had written as a very young man, remained the key note of his work. His life became much quieter now and ‘infinitly less social,’ allowing his painting to come forcefully to the fore.

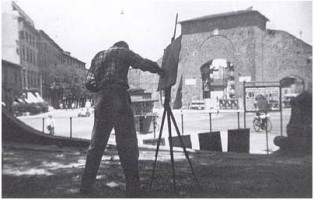

- In the Fifties, painting in Piazza di Porta Romana

Outwardly, Staude was a family man (his son Jakob was born in Germany in 1944, in 1947 Renate and the children had returned to Florence), who made his living by teaching painting and history of art at the American colleges on the hills of Bellosguardo or in his own studio in the Via de’ Serragli 148. He was a born teacher and loved to teach. To teach means to communicate, to teach means to pass on: to him, two of art’s main functions. ‘Being constantly surrounded by people who wish to learn relieves one of that feeling of loneliness that often befalls an artist,’ he said in his last year to the journalist Neera Fallaci. Through his courses in history of art he was able to keep up an almost daily conversation with the masters of the past. He called them ‘my ancestors’ and drew from them much encouragement and inspiration.

- Staude with his pupils of the College in Bellosguardo

One of the most brilliant young people among those attending classes at his studio was Lorenzo Milani (1941), the famous future rebel priest. When, in the matter of a year, the young man decided to take the vows of priesthood, he thus explained this decision to his former art teacher: ‘It’s all because of you. It was you who spoke to me of the necessity to search for the essential, to eliminate all details and to simplify; to see every subject as an entity in which each part is connected to the other. I was not satisfied by looking for these relationships among colours alone. So I chose another path.’

Staude felt surer and surer of the “path” he himself had chosen, in spite of the fact that the art that was fashionable in his day did not seem to prove him right. “The solitude in which I place myself by breaking with all those who are in fashion, freightens me less and less”, he wrote to his mother. None of his almost annual personal shows were particularly successful and he remained fairly isolated among the crowd of painters. For one who kept dreaming of the role that the artist had played in the society of the Renaissance it was a painful situation. But he consoled himself by thinking of Cézanne, who had so much hoped that at least one of his paintings would be exhibited at the Paris Salon and who had been equally disappointed.

Still, there were many who appreciated Staude’s art. The modern art gallery of the Pitti Palace in Florence purchased five of his paintings; the Uffizi bought one drawing and a self-portrait for its prestigious “Galleria degli autoritratti”; European and American collectors came to his studio and hundreds of paintings were thus sold.

His life, though never easy, remained rich and varied. Music played in the large drawing room at the Via delle Campora (when emigrating to the US, Maya Winteler had left him the grand piano that her brother Albert Einstein had given her and which she had played together with Staude), journeys, encounters and conversations with both the most humble and the most cultivated people of his time contributed to weave that ‘lovely spider web’ as which he described his life as it was drawing to a close.

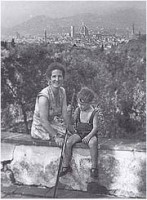

-

Renate with her son Jacopo

in the fields near the house

His yearly summer holidays in Rome or Venice – two essential steppingstones in his art – caused him gradually to abandon the ‘noble grey green of Florence’ by introducing him to more voluptuous shapes and colours.

In order to be able to paint them in all its transparent luminosity, in 1955, during a long Roman working holiday, Staude took up pastel. With this medium, which in the course of the years he would develop to unusual perfection, he produced some of his best work. But when he tried to translate the lesson learnt from pastel into oil, he came up against huge technical difficulties. His serious nervous breakdown in 1957 was caused by this exhausting struggle for a more refined technique, by the persistent lack of public recognition, and by yet another disappointment in an artist friend, the young German sculptor Hans Kaunat, who had failed him in his hope that together they might form a persisting artistic community.

-

The sculptor Hans Kaunat, 1956

Drawing on paper

Yet, Staude persisted in his ceaseless endeavour to translate onto canvas ‘what has been on my mind for such a long time,’ as he wrote to Françoise d’Origny Simon, a pupil and friend from Paris.

In 1956 an exhibition of his own paintings lead him back to Hamburg. As the old world unfolded before his eyes, he found it to be unexpectedly familiar: ‘I shall try now to stand with two legs on this beautiful world: Florence and Hamburg,’ he wrote to Christopher Norris.

In 1962 his mother died and the last beloved link with the happy and colourful world of his Haitian youth disappeared with her.

In 1963 the Accademia delle Belle Arti of Florence organized an important retrospective of Staude’s work. It was presented in the catalogue by Ulrich Middeldorf, the Director of the German Institute of History of Art in Florence, a renowned scholar and one of Staude’s most consistent admirers, and attracted, if not the attention of the official art critics, at least that of new fans and collectors.

In the same year Staude began to transform the plot of wasteland that surrounded his studio in the Via de’ Serragli into a garden. This garden, with its bushes and flowers, was to become the subject of his last paintings. Here his last and dearest pupils gathered: four or five young Florentine men with no formal education whose devotion accompanied him till the very end. He briefly even dreamt that “The Garden” might become the name of a new artistic movement. In 1966 he presented his work collectively with that of his pupils and the sculptor Hans Kaunat at Florence’s Galleria III, but when the exhibition failed to be successful, that dream also faded away.

- Playing piano at his home in Via delle Campora

Ever since the beginning of his Florentine life, Staude had chosen his models from among the simple people. Peasant women, car park attendants, road-sweepers, shoemakers, innkeepers and artisans had interested him for the anonymous monumentality of their Mediterranean heads. ‘I keep trying to attract these figures to my studio, as it is because of them, really, that I have remained here,’ he wrote in 1957 to Heinz Theuerjahr, a sculptor friend. In the Sixties those very same ‘figures’ began to interest him – or ‘to concern’ him, as he said, – not so much for their heads, but for ‘their daily attitudes.’ He thus painted The Man in the Tram, The Cyclist, The Girl with an Umbrella, The Man with the Newspaper, The Gardener, The Road-sweeper, and many others. Also the series called “Le Cascine” (1962-1966) after the park in Florence where they were painted – bodies of men and women lying peacefully in the grass, playing or reclining beneath trees – was the result of this diminishing interest in the individual, this ever-growing passion for colours and shapes.

- In the garden of the studio with his pupils

In 1965, when the acrylic paints appeared on the market, Staude’s technical problems were solved. ‘Finally I have found in the acrylic tempera a material that suits me […]. The painting acquires a luminosity and a transparency as I was never able to achieve it with oils,’ he wrote to Olaf Oloffson.

In the summer of 1966 Staude went to Castagno d’Andrea, a small mountain resort in the Tuscan Apennines. His intention was to take a rest. “Mountain landscapes – who has been able to paint them well? I only know of the East Asians,” he had written to his mother in 1957. Now it was precisely the challenge of ‘all those greens’, combined with the complete absence of man that fascinated him. Thus, he immersed himself in the very subject that he had always considered un-paintable. ‘How many times do I still have to fall in love with a place? […] I feel bewitched!’ he wrote to Christopher Norris. He returned to Castagno for four summers in a row, saying that the landscape reminded him of the mountains of Haiti.

- Painting in the Apennine near Castagno d’Andrea

While in both Venice and Rome Staude crept returning to a group of friends and artists who unfailingly welcomed him with affection, at Castagno he became a solitary figure. In the morning he would leave his rented room and walk with his easel towards his motifs – hills, trees or a rooftop against the distant mountains; in the evening he would exchange a few words with a holidaymaker at the village’s only bar. ‘My days consist of (five or six) hours of work and hours of tiredness,’ he wrote to his daughter. ‘I sweep my room, do my laundry and talk to the bus driver who arrives at one and eats with me.’

In fall 1968, he left for a long, wonderful trip through Europe to paint a series of portraits. It brought him back to Paris and Hamburg: ‘A very precious recollection.’ From 1970 onwards, he spent even the summer months in Florence, painting. He painted hippies, the new long-haired young people in their disorderly poses, as well as his beloved garden whose plants grew so exuberantly that people would say they looked tropical, ‘Haitian.’

The man with whom Staude talked about all this, art and life, was Giorgio Colli, the Italian philosopher known for the definitive critical edition of Nietzsche’s work – his last friend.

Painting no longer worried him with its problems. He felt he had solved them: ‘I think I know now how to do it.’ The paintings of the last ten years, with their ‘angry look,’ as he once called it, proved it. He had given them a dash of sensuality – the very same sensuality that had been inhibited at his first encounter with the stern Florentine landscape.

A good deal of work had been done and his sensitive mind could calm down. It was like a slow settling of accounts, like getting ready for life’s conclusion. He said of himself (just as Cézanne and van Gogh and Marées and so many others before him) that he hadn’t done much more for painting than continuing its tradition and opening up a new path for it. ‘Perhaps there will be some people (also among the young) […], who will accept my suggestion that the best part of painting is looking. And that looking will take us much deeper than rationalizing; that inventing is the same as looking, observing creatively; that the appearance and its meaning are one and the same,’ he wrote in 1972 to Herbert Schmidt-Colinet. And to Christopher Norris: ‘Perhaps my paintings can indicate the direction in which it may be worthwhile to persevere.’ This was what at the age of thirteen he had promised he would try to do. “And in the end, life is the finest poetry”.

In 1972 it seemed that his efforts were to come together also before the public eye: a large exhibition in Hamburg was organized with the help of his banker friend, Eric Warburg. Staude – now sixty-seven – prepared for it with the same excitement that, at nineteen, he had felt before his departure for Munich. The idea was to return to the city he had left fifty years earlier and show it that he had fulfilled his artistic promise.

That exhibition opened to a grotesque, almost tragic spectacle. The paintings were held up at the Italian border and the opening took place in front of bare walls. Staude felt, he had been pierced “by the poisoned arrows of voodoo.”

A year later he died in Florence. ‘One should become invisible behind one’s paintings. The work should be in the foreground; not oneself,’ he had written in one of his last letters to his daughter.

- Staude and Florence

This article is an extended version of the biography which was published in the catalogue oft the exhibition at Palazzo Pitti in 1996.

Chronology

| 1904 | Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, the second son of German parents. |

|---|---|

| 1909 | The mother moves with her two boys to Hamburg. |

| 1918 | Begins to draw. Sees the first big exhibition of Edvard Munch in Hamburg. Inspired by German Expressionism, he joins the painter Schmidt-Rottluff of “Die Brücke.” |

| 1921 | Rejects Expressionism. Begins his life-long observation of nature. |

| 1923 | Studies painting in Munich, then spends half a year with his father in Haiti. |

| 1924 | Hamburg. Studies with H.E. Schnegg, a late German impressionist painter. |

| 1925 | Painting trip to Italy with Schnegg and his students. In Florence he decides to leave the group and remain in the city. |

| 1928 | Returns to Hamburg. Renewed attempt to paint in the North. |

| 1928-29 | Paris. Studies Cézanne and the French Impressionists. Meets the sculptor Ludwig Kasper, who becomes a decisive influence on his art. |

| 1930-42 | Becomes involved in the dazzling international life of the city. Belongs to the cultural circle of Maja Winteler-Einstein and Bernard Berenson. |

| 1935-38 | Paints at the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Florence as a student of Felice Carena. |

| 1938 | Marries the architect Renate Moenckeberg from Hamburg. |

| 1938-42 | The first students come to his studio. Successful exhibitions in Florence, Milan and Rome until his conscription into the German army. |

| 1945-73 | Paints and teaches in Florence. In the summer he paints either in Venice or Rome, later in the Tuscan Apennines. Develops a personal pastel-technique. Almost yearly one-man shows in Florence, Venice, Rome or Milan. Also in Hamburg (1956, 1972) and Cologne (1957). European and American collectors visit his studio. Over the years, the Pitti Palace acquires five paintings, the Uffizi one drawing and a self portrait. |

| 1963 | The Accademia delle Belle Arti in Florence honours him with a retrospective. |

| 1972 | Last major exhibition in Hamburg. |

| 1973 | Dies in Florence on July 23 and is buried in the Cimitero degli Allori. |

| 1996 | The Palazzo Pitti in Florence organizes a major exhibition of his work (with catalogue) as a document of the Novecento Italiano, the Italian Modern Classic. |

| 2001 | Personal exhibition at the Spandauer Zitadelle in Berlin. (With catalogue) |

| 2015 | Exhibition and scientific conference at the Giorgio Cini Foundation in Venice |

Personal exhibitions

| 1938 | Florence, Galleria Schacky |

|---|---|

| 1940 | Florence, Lyceum |

| 1942 | Rome, Galleria di Roma |

| 1942 | Milan, Galleria Duomo |

| 1948 | Florence, Galleria Michelangelo |

| 1951 | Florence, Galleria Vigna Nuova |

| 1955 | Florence, Galleria Spinetti |

| 1955 | Rome, Galleria Il Camino |

| 1956 | Hamburg, Italienisches Kulturinstitut |

| 1957 | Florence, Galleria Vigna Nuova |

| 1957 | Cologne, Italienisches Kulturinstitut |

| 1959 | Venice, Galleria Santo Stefano |

| 1960 | Padua, Galleria Le Stagioni |

| 1963 | Florence, Accademia delle Arti e del Disegno |

| 1965 | Florence, Saletta Gonnelli |

| 1966 | Florence, Galleria III |

| 1968 | Florence, Saletta Gonnelli |

| 1969 | Florence, Galleria Vaccarino |

| 1971 | Florence, Il Mirteto |

| 1971 | Florence, Galleria Vaccarino |

| 1972 | Hamburg, Italienisches Kulturinstitut |

| 1996 | Florence, Galleria d’arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti |

| 2001 | Berlin, Zitadelle Spandau |

| 2001 | Hamburg, Handelskammer |

| 2015 | Venice, Fondazione Giorgio Cini |