Essay

The Slow Eye

On the works by Hans-Joachim Staude

By Thomas Baumeister

I. Introduction

Hans-Joachim Staude stood firmly by the classical idea of painting at a time when it was widely held to have long had its day. Anyone who examines his works with care will not fail to detect traces of Monet, Degas and Cézanne and their theories. In his earlier works he took inspiration from Velazquez and Hans von Marées. Alternatively there are echoes of Renaissance portraits, of Piero della Francesca and Masaccio. Sometimes one feels reminded also of Chardin and Corot. Throughout his life he dedicated himself to the task of preserving and renewing the art of painting in the classical sense. Thus it was that he kept up a conversation with the great painters of the past, without, however, specifically imitating them. For him ‘painting’ was not a passing art-historical phenomenon; nor was it a progression that had reached its peak in the great French masters of the nineteenth century, never to be surpassed. One may say that for him, rather, painting remained, as with Balthus, a living ideal that rides above temporal vicissitudes and remains untouched by them.

By ‘painting’ one must here understand first and foremost the art of ‘transfiguration’, the transformation of a piece of the reality around us into a colour weave, into a self-sufficient object, an ‘image’. An unfailing interest both in visual appearances and in the image as a reality in its own right, with a law of its own, creates a tension which Staude continually probes in his theoretical notes. The desire to remain true to the appearance and at the same time to give expression to the picture’s intrinsic force, or indeed its beauty, demanded a balancing act that Staude had to perform anew with each painting. His aim was not to copy natural appearances but, as he liked to put it (quoting Cézanne), to achieve ‘a harmony parallel to Nature’s’.

-

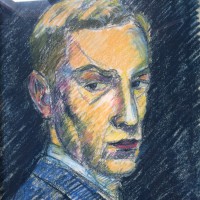

Self-portrait as a young man, 1922

Chalk on paper

-

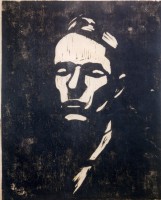

Portrait of Fritz Rougemont, 1922

Woodcut

As a young man Staude initially stood close to expressionism, which in his view pressed closer to the heart of reality than impressionism, which could render no more than a segment of it. The German variety of impressionism, with its slapdash brushwork, held particularly little attraction for him. In the spirit of Hans von Marées and Conrad Fiedler, the individual observation (“Einzelanschauung”) was only the first step on the way to representing a general law.

Staude’s link with contemporary revolutionary artistic movements was, however, short-lived only. There were plenty of reasons and inducements for his not pursuing this line any further. Alongside an innate aversion to strident effects (as in Van Gogh’s followers, for instance) there was more than anything else a conviction that an individual artistic language could only develop through a wrestling with an opposition, through a slow wrestling with the reality in which we live. Only ‘Nature’, so he believed, protected him from the two risks which he considered his fellows ran: slipping into the ornamental, and falling victim to an outworn set of stylistic patterns, such as cubism or futurism. ‘Modern paintings,’ Staude observes in notes that date from the late ‘twenties, ‘are often not concerned with the representation of an actual thing, but with like-this-representation,’ Their ‘like-this’, furthermore, is a ‘like-this-as-it-was-in-X-or-Y..’ He maintained that responsible painting must constantly take the thing itself, Nature, as its starting-point, otherwise it will degenerate into arbitrary stylization. Quite often Staude considered whether the principles of form might not be put into effect independently of natural models, i.e., in non-figurative painting. His instincts, however, drew him in another direction. The art of transformation only works where there is something that can be transfigured.

In considering how Staude and many a like-minded painter of the modern age decided on a return to the figurative, or had else been faithful to it all along, one must also bear the following factors in mind. Firstly, the perplexing pluralism of the art scene during the first decades of the twentieth century, and the lightning pace of it. Cézanne’s late work had scarcely been discovered when Braque and Picasso were on the point of revolutionizing the whole pictorial framework with their ‘cubist’ paintings. At this stage, moreover, the chaff had not yet been winnowed from the wheat: people were simply unable to tell any difference between the important works of the modern age and the lesser. There was, and still is, an aping of the modern. Finally one must not forget that the revolutionaries of modern art were a generation older than Staude. Kandinsky, to take one example, was his senior by thirty-eight years. What is more, these painters had themselves prepared the way for what they experienced as contemporary art. It thus became clear that for those who wanted to emulate the masters of the modern age it would be ill-advised to tag on to the ready-made achievements rather than strike out in quest of something that they could truly call their own, deriving from experience. At the same time, in keeping with a common psychological mechanism, there was an obvious urge to revert, as it were, to the generation of the grandparents – to the generation of Hans von Marées, Cézanne and Degas.

II. Florence

It was, however, due more than anything else to Staude’s encounter with the city of Florence and the art of the Quattrocento that all he had vaguely conceived and sought would crystallize into a clearly defined goal. Contact with the great art historian, Bernard Berenson, who had developed a keen eye for the ‘tactile values’ in fifteenth-century Tuscan and Umbrian painting, an acquaintanceship with like-minded Italian painters in his vicinity (Carena, Cavalli)[1], and, even more, his encounter with the important sculptor, Ludwig Kasper, strengthened Staude in his aim: the transformation of reality into what Kasper called the ‘great’, the self-sufficient form.

Staude had often recounted how a short study trip to Italy, which he reckoned would last a few weeks, grew to three years (1925-28) and eventually became a lifelong sojourn (1929-73). It could well be that his decision to settle permanently in Florence was influenced by the fact that the Central Italian landscape and the prevailing climate were more akin to tropical Haiti, where he had spent his early childhood, than the coolly temperate Hamburg. Yet other factors were of even greater significance: in the ‘twenties of the previous century, a young, susceptible man’s encounter with the art and scenery of Florence and Tuscany still had the character of a genuine discovery [2].

Staude discovered not only an art and a nature of a special stamp but also a way of life, or various ways. A way of life that had an aristocratic mould, not to the exclusion of a cultural aristocracy, under the roof of Berenson, Hildebrand or Maja Winteler-Einstein; and a culture of the countryside and crafts, where Spartan simplicity, down-to-earth wit, charm and feeling for distance were attractively combined. No less impressive was the Tuscan landscape. Shaped by the hand of man and built on, yet free of trivial innovations, it had an educative impact on one’s grasp of form and quickened the eye for the great and the wonderful. Most of all, however, this landscape stimulates one’s responses to colours, and does so in a remarkable way: not really because it is picturesque in the popular sense of the word, but on account of the light and also the multiple effects of colour, which come into their own in Spring, Autumn, and also in the Winter months, and which can only find their equivalent through the medium of painting, not drawing.

-

Giuseppina with head cloth, 1939

Oil on canvas

Last but not least, it was Staude’s encounter with the art of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that had the mark of a genuine revelation. While the educated German middle classes were acquainted with Raphael, Michelangelo and Correggio, the artists of the early Renaissance remained largely unknown: But it was Giotto, Masaccio, even Ghirlandaio, and more especially Piero della Francesca who captivated the young painter. In this connection it deserves emphasizing that the art of Piero della Fancesca was then virtually unknown, even among scholars; at any rate, he did not enjoy that immense prestige that was subsequently to come his way. The earliest monographs of any substance only appeared in the later 1920s. Staude’s discovery of the Piero frescoes in Arezzo and his attempt to take this painter’s language of forms on board are not to be seen as a return to an established tradition. They smack rather of innovation, adventure, nay, of the modern. The discovery of the great art of the Quattrocento pointed Staude the way to a marriage of the extremes of the ‘real’ and the ‘irreal’ which in his view was forgotten by the artists of his day, and which promised him the chance to bring a new form of ‘modernity’ into being.

The discovery of a new province of reality, of a new streak of land, had, at the time when Staude’s artistic aims were being formulated, a metaphysical meaning, especially for the young. The poetically and artistically inclined (especially if they were familiar with the German-speaking world and had read Rilke’s Florentine Journal) saw works of art and the beauties of nature not just as pleasing accessories to brighten things up; rather they made claims for them that were ethical and metaphysical. European Romanticism, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche had declared art to be mainly a metaphysical activity. And this creed molded Staude’s convictions as well as those of many artists of the avantgarde. In the masterpieces of art and in the works of Nature, in the silence of the landscape, in the human form and the human countenance appeared the riddle of man and existence, something which might perchance be momentarily revealed. Whoever, in the manner of a painter, dedicated himself unreservedly to visual appearances and sought to decode them was on the scent of this great and mysterious context.

III. Florentine reminiscences

From the end of the 1920s till his death, Staude lived at first alone, later with his wife and children, in a house on the hills at the southern edge of Florence, called the Villa Strozzi-Machiavelli. Situated right on the Via delle Campora, which till recently was largely traffic-free, it had been built around a square mediaeval fortified tower.

-

The house in Via delle Campora seen from the fields, 1950

Oil on canvas, cm 61 x 81

It stands scarcely a half-hour walk from the centre of town, yet even in the 1960s its rear windows still looked out onto farmland. One found oneself in the peace of the countryside, broken only now and again by a passing car or scooter, or the characteristic hoot of a distant bus horn. While the city swarmed with tourists, nobody ever wandered up as far as here. The sunlit gardens and fields which were visible from the first floor – from the road they were hidden by walls – provided a surprising contrast with the city centre, which, in its stone cladding, is typically Tuscan: a hard kernel, surrounded by the green of gardens and parks, fields and olive groves. They constitute both its antithesis and its complement.

-

View from the window of the dining room, 1938

Oil on canvas

The dining-room window looked onto the farmhouse opposite and the mediaeval monastery with its arcades in the background. If you leant far out, you saw the flat valley of a stream, which drifted far to the south. Here you could wander, not a fence in sight. This was to experience childhood all over again as one dawdled in the countryside along a willow bank. In the Spring this whole scene was a mass of flowers: wild narcissi, tulips – a rustic paradise out of Dante. To the south were hills on whose crests a convoy of pines treaded steadily along.

The family at the farm opposite were friends. Staude immortalized their daughter Adriana, a young girl of sphinx-like reserve, in many of his finest pastels and oils. The farmers have gone by now, the farmyards have been asphalted over, and farmhouses along the Via delle Campora have been converted into suburban villas, more or less successfully. All is not lost. The view one had from the dining-room, especially in Spring, is still unforgettable, as when seen for the first time. The triad of the dark brown of the freshly ploughed fields, the emerald green of the previous year’s meadows (not forgetting the bright green of the vines in orderly rows) and the incorporeal grey-green of the olive trees has preserved its incomparable power to enchant. August offers quite another picture: open the shutters at midday and the trees are a white blaze in the silvery summer heat.

-

Adriana in blue, 1957

Pastel on paper

The rural tranquillity was all-enveloping once one had left the crowded Via Senese and begun to climb. A steep, stony road, the first half of which is now packed with scooters, cars and skips. Not a single blade of grass grows between the paving stones, which, together with the walls to left and right creates an unbroken, and, as it were, hermetic entity of stone. It is as if one were advancing between the walls of a canal that had been emptied and saw nothing but branches of olive trees, a gateway, the ridge of a roof. On the whole, however, there is no looking right and left. It is equally impossible to let one’s thoughts wander at liberty. To be hemmed in by these walls is to find one’s thoughts to be channelled, too. Undisturbed, one is capable only of thinking about what lies behind one, and, especially, what lies ahead. Here it almost seems as if one were alone on life’s journey. Staude threaded his way countless times between these walls on the way to his studio and back. Their earnestness and their beauty harmonize with his work, which was created in ever greater isolation and loneliness.

-

Via delle Campora, 1956

Pastel on paper

Staude always made for the rooms on the upper floor of his home, which would be darkened against the heat. In the music room there was a grand piano on which he played every evening. It stood in front of a single, very tall window, where the gaping void of the sky was spread out like a blank luminosity in an otherwise dark room.

IV. Form, colour, light

Staude saw his life exclusively as a painter’s. There are, to be sure, plenty of drawings by him, studies and preliminary outlines, but he only ever looked upon the pencil as a means to an end. Sketches, the art of capturing something at speed, were not his way: he abhorred all that was dashing or merely brilliant. For him, painting was a slow art, indeed the art of slowness, of deceleration, which should bring its subject-matter to a halt, or, better, to an enduring present. The art of painting has long been regarded as an art of the long breath, of thorough observation, of long preparation. From the careful application of colour, layer upon layer, from undercoat and overpainting – and painting is essentially the art of overpainting – the object emerges as a coloured fabric (tessuto, an Italian expression that Staude rejoiced in using). It is this modus operandi that enables a spatial and temporal depth to be given to a picture [3]. Staude took pains to avoid the ‘superficial sensitivity of the trademark’. ‘Sensitive’, as he noted, ‘is not the manner in which one puts something down, but the slow (i.e., carefully prepared) outcome when the final layer of colour has been laid.’

-

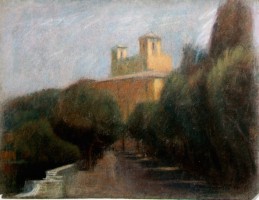

Sant’Ilario in the spring, 1938

Oil on canvas, 38 x 52 cm

It is handed on that Staude and Hans Purrmann painted

this view side by side from the garden of Villa Romana.

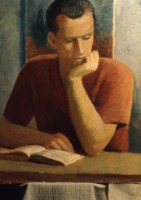

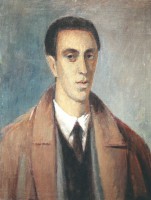

Staude continually sought to locate his own painting in the context of other artists. He was on friendly terms with Hans Purrmann, and there are congruencies in their subject-matter, though in style and temperament they are worlds apart. The ‘great’, plastically conceived form, for which Staude strove, as did Kasper too, was not Purrmann’s concern. Apart from Kasper, Cézanne leaps to mind, about whom Staude writes: ‘…if one enquires into the ancestry of this [my] style, Cézanne’s name springs to mind; to him I owe the consistently clear cubist formulation, which arises from colour relationships.’ (…) Cézanne’s ‘clear volumetry’ had forerunners, he said. Especially in the heads of the early Italians of the quattrocento, but also, be it added, in Piero della Francesca’s figures. Something has been gleaned from Carl Hofer’s ‘theoretical intentions, especially in the pictures with people in them (Staude is here referring to his own pastels.) (….) But there is no model to be had in Hofer’s coloristic “impoverishment”‘. A striving after a rich chromatism links Staude with Cézanne, he wrote, even if Staude’s handling of surfaces rejects ‘the multiplicity of facets’ – see for instance the Young man in a red shirt.

-

Young man in a red shirt, 1954

Oil on canvas, 62 x 50 cm

These observations, above all the last one about Cézanne, tell us a great deal about Staude’s artistic intentions. In conversation he once gave me to understand that he could not follow Cézanne in his perception of light and shade, his elimination of shadows. In actual fact he too tried, in the spirit of Cézanne (and Degas), to translate the modeling (errore tipografico) of light and shade into chromatic relationships, nevertheless keeping closer to nature than Cézanne did.

Staude speaks about the French painter’s faceting of surfaces and thereby reveals how different his understanding of form is from that of his great exemplar. His own starting-point is the volume, the individual thing or an assemblage of things as a more or less closed mass, while in Cézanne the closed masses are fragmented into chromatic relationships, which, in turn, are far removed from those of the impressionists. Cézanne is not facetting closed volumes as if to make polished diamonds of them. That would better describe the early cubism of Braque and Picasso. Rather things come into being from colour, from a free, largely achromatic texture of brushstrokes, created anew. And, it is as well to note, this is achieved to a considerable degree by avoiding the illusionary impression of space. That is why Cézanne no longer spoke of the modelling of form but of chromatic modulation; of rows of colours and colour variations which spread out in parallel ribbons of brushstrokes, extending beyond the edges of things. Staude on the other hand tends rather to model with colour, colour that especially in the late works achieves a luminous power, ‘without diverting into self-glorification’ (Notebook 37). Richness of colour and the clarification of volumes and masses into a kind of glowing ‘volumetry’ are typical of many of his important works.

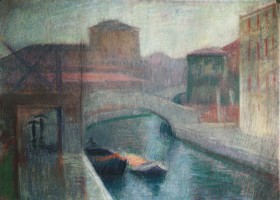

Staude was not, however, concerned solely with the richness of the colourful appearance, which can take one into dissonance, but equally with the creation of chromatic balance. So it was that he loved, especially in landscape painting, to do as the old Italians did, covering the canvas with a ground of red or ruddy-brown, whereby the green of trees and landscape was on the one hand broken and on the other heightened. In portraits, contrariwise, he liked to let the green undercoat show through. On this aspect of his work he writes (Notebook 37): ‘Just as I look for the red in the green, so also I look for pink and shades of green in the blue of the sky, and green in the red of roofs.’ Staude’s use of colour becomes an art “des kleinsten Übergangs”, of minimal transition (a phrase of Adorno’s, with reference to the music of Berg) and of chromatic totality. ‘The masses of light and shade, as they play one against the other in countless street scenes, are always felt as colour relationships, whose difference in value keeps diminishing’ (Notebook 37). This technique leads to astonishing results. For instance, works that are restrained in their colour scheme, even to the point of being ‘tone painting’, reveal on closer inspection an inexhaustible chromatic polyphony and luminosity. (See, for example, the muted pastel, Venice in the rain.)

-

Venice in the rain, 1957

Pastel on paper, 47 x 65 cm

Staude’s understanding of colour and form must, first and foremost, be considered in relation to the way he sees light. Here again the comparison with Cézanne proves instructive. In Cézanne there prevails a tendency to eliminate natural light. Hence his paintings’ great luminosity, in which the ‘objects’ appear to be illuminated scarcely more brightly by the sun, than by the light that springs from the painting itself. Staude’s passion, on the contrary, is for the cast of light on things – always the light of nature, let it be noted. His pictorial world tirelessly investigates the destiny of light, its dawning, and its waning too, even to the point of expiry. This enthusiasm for a light on things that can turn into a light in things, links Staude’s intentions, despite every difference, with Morandi, who, in his still lifes, knew that the dust and the light on things were more important for him than the objects themselves.

Staude’s concept of form is bound up with his love for the play of light. In conversation and in his notes he would frequently stress the abstract, non-figurative character of his figurative art. It is an abstraction that is nonetheless culled from Nature – an abstraction, a simplification of form, that light itself performs on things. This brings us to the very rub of Staude’s artistic intentions. The striving after a greatness of vision, after the great form (in Marées’s and Kasper’s sense), has eternity as its goal, the goal of transforming things, people and landscapes into what is enduring. And yet, through the silent speech of light, time too thrusts into this world of durability, bringing about mutability and impermanence. This tendency to look for the eternal intertwined with an awareness of the caducity and fragility of things is perhaps what is most typical of Staude, or at least one of the essential aspects of his work. Light in the art of painting was therefore decisive for him, light in its dual capacity: bestowing a heightened reality on things, and, by growing dim, depriving them of it again.

V. Pastels

Pastels, a medium in which Staude achieved mastery, suited this endeavour to a remarkable degree. It lends itself to working rapidly. Pastels are highly sensitive, like butterflies’ wings, and difficult to protect and conserve. On the other hand they can remind one of certain effects of monumental painting, of wall painting. (For instance, his figure compositions in Le Cascine, the city park of Florence [4], or the Standing young boy, see Gallery, come to mind.) As with fresco, so it is with pastel, the surface over which the chalk is drawn being rough and bumpy. In order that the chalk dust may adhere, one must use long-fibred paper or cardboard, which is usually coloured. Staude favoured a neutral grey so that he could act out his play of colours upon it, and fulfil his ambition to simplify forms.

-

Le Cascine: Three young people in the grass, 1964

Pastel on paper, 68 x 99 cm

Pastel has further qualities, and these too must be called to mind. For one, it has none of the shine (obtrusive at times) of oil paint. Rather the colours are muted, thereby allowing, however, for remarkable chromatic intensity. (See, for example, The little white house in Rome (see below), and San Geremia in the morning in Venice.) Besides, the grains of pastel have a gleaming quality. Kissed by light, the colours give forth a glow that is all their own.

-

San Geremia in the morning II, 1957

Pastel on paper, 47 x 65 cm

The light from watercolour is quite another thing, as conceived by Cézanne, for example. In the watercolour as a physical object, light, regarded as a source of illumination, plays no more than a minor role. It resides rather in the white, abstract light of the paper, which shines through the transparent colours or else lies completely bare, so that the object itself is transformed into an epiphany of light, and thereby becomes that much more an expression of it. As we saw, for Staude, unlike Cézanne, the division of light and shade on things remained an undisputed subject for painting. Yet this interest (in light as subject) also finds its counterpart in the physical characteristics of pastel. In its glow and lustre are fulfilled those destinies of light within the medium. They become the theme of Staude’s painting. Thus his pastels are not just a representation of light. Rather they achieve independence, as with Cézanne, if in a different way – becoming nothing less than manifestations of light and colour in their own right. Hence it may very well be that this art takes its place within what we call the modern.

In the context of Staude’s pastels, another name than Cézanne’s must now be cited: Degas. Degas found that pastel had gradually become a forgotten medium during the course of the nineteenth century. The early decades, to be sure, had seen Constable, Delacroix, Turner and Menzel turning to it, but only occasionally. Degas raised it to a new perfection. One may say indeed that he actually created a new concept of working in it. Without his example, Staude’s achievement in this field would be almost unthinkable. A glance back at the history of work in pastel may shed light on what is so special in Degas’s method. Pastel in the eighteenth century, as with Maurice Quentin-La Tour, the Swiss Liotard, Perronneau, etc., generally meant portraiture. Its practitioners were travelling artists for the most part, who were able to fulfil the growing demand for portraits, employing quick and relatively inexpensive means. Maurice Quentin-La Tour is chiefly known for his brilliant pastels, which catch the witty, smiling, society folk of his day. Liotard strives after a greater roundedness of form, and surprises us with his unconventional and unified colour schemes. Occasionally he calls Staude to mind, as in a very modern-looking, large landscape in pastel (Rijksmuseum Print Room, Amsterdam). Chardin’s rare, very important pastel portraits bring us close to modern ways of seeing, too.

In the nineteenth-century pastel, it was the element of draftsmanship and the quality of the sketch and the preliminary study that finally prevailed for the most part. First, Degas developed this medium as a new pictorial genre. Unlike Manet in his pastels, which, be it noted, are more in the way of occasional pieces, Degas arrives at a deep-seated oneness of drawing and painting [5]. His pastel technique ‘starts with the stroke (…), certainly not with the coloured surface.’ He does not employ ‘colour illusion but a play of lines, using complementary and conflicting systems of strokes.’ The overlapping of these areas of strokes is subsumed into a dense, colouristic structure, which corresponds far more closely to the manner of applying paint than do, for example, the oils of Van Gogh, who frequently tends to draw with the brush rather than paint with it. Degas’s continual build-up leads to fresco-like effects. The vertical layers of strokes, with their trickle effect, can give the impression that a shower is flowing over the surface.

Although Staude’s pastels are more transparent in manufacture than those of the late Degas, and although he was governed by different ideas of form, for him too the ideal of the density of paint was paramount. His means was the bunching and crisscrossing of vertical and horizontal hatching. The pastel stroke, unlike oil or acrylic, allows the artist to combine a maximum of chromatic complexity and mobility with formal unity, and, as required, with restraint in colours or its opposite. A pastel such as Venice in the rain (above), though presenting itself almost muted in colour, proves to be a cosmos of virtual colourfulness in which the daedal values of orange, salmon pink, grey-blue, turquoise green, mauve, etc., combine in variation after variation, but without ever becoming strident. At times Staude will also use the length of the crayon to produce coloured ribbons of great luminosity – see The little white house (Rome), and Campo San Barnaba (Venice).

-

The little white house, Rome 1955

Pastel on paper, 48 x 63 cm

-

Campo San Barnaba, 1960

Pastel on paper, 45 x 63 cm

In the emancipation of colour and the bold chromatic combinations that typify his later works, lies one of the reasons for his modernity. His rich output in pastel, which embraces landscapes, cityscapes, figures and portraits, unquestionably belongs to the most important of its kind in the twentieth century.

VI. Portraits and figure paintings

Portraiture and figure painting play a significant part in Staude’s oeuvre. In keeping with his classical predecessors, the human figure and face remain with him one of the most important subjects in the fine arts. We are, needless to say, concerned here with subjects that impose certain limitations on artistic freedom and the free play of colours, if only on account of the demand for a likeness.

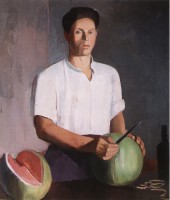

In Staude’s portraits and figure paintings one often detects a tendency towards plastic isolation, which may be due not only to personal inclination but also to the influence of the sculptor Kasper. For example, Young man with watermelons, despite all the beauty of colour, has an abstract, carved stillness, the unity and reserve of a statue. The same applies to Young man with a pole (Venice 2015) in which we can discern, allowing for the time gap, an echo of Piero’s frescoes at Arezzo. Now and again, clearly in emulation of Cézanne, he borders on expressionlessness and reification. Especially worthy of attention is The chimneysweep in the Pitti Palace. We find ourselves facing a giant who appears lost in a dream. It is most beautifully painted, with a transparency that is characteristic of early Staude.

-

Young man with watermelons, ca. 1931

Oil on wood, 87 x 75 cm

-

The chimneysweep, 1936

Palazzo Pitti, Galleria d’Arte Moderna

Oil on wood, 175 x 87 cm

On closer examination, the range of expressive means in Staude’s portrayal of people reveals a rich diversity. Nonetheless, an underlying solitude prevails. Apart from works of an austere and sober cut (for instance Self-portrait in a black beret (see Gallery) or portrait of Signora Vagaggini), and the important portrait of Gino Gerola, all pictures of great firmness and objectivity, though without the sharpness of the Neue Sachlichkeit, there are sophisticated portraits such as that of Nicky Mariano, the lady who kept house for Bernard Berenson in his later years (see Gallery). A mother-of-pearl shimmer lends a peculiar fascination to the painting, regrettably unfinished. An earlier, almost insouciant variation of Staude’s art of portraiture is Young Man in a Red Waistcoat (Venice 2015), who, seen from below, fixes the viewer with a severe stare.

-

The poet Gino Gerola, 1951

Oil on canvas, 70 x 52 cm

-

La Signora Vagaggini, 1929

Oil on cardboard, 73 x 60 cm

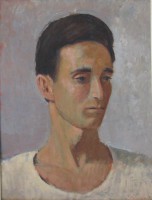

The portraits of Felice, a local butcher’s boy, recall those late antique faces from the Fayum mummies, alternatively the figures in Renaissance paintings. In Italy Staude derived a special pleasure from getting to know such types in natura, having already met them in the works of the great masters. Here art and reality merged. Hans von Marées treads similar ground in a letter he sent from Florence to Count Schack: ‘I then leave the chapels in question, and there, at no distance to speak of, I see in front of the altars, behind the pillars or doors the selfsame figures that those Old Masters painted.’ [6]

-

Felice, 1950

Oil on canvas

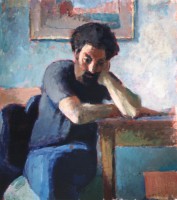

This especially applies to the portraits of the above-mentioned Adriana, a local peasant girl. To her we owe not a few Staudes of classical stamp, both oil paintings and pastels. Beauty, pride and reserve came together in her. Here was some unfathomable being by whom Staude felt drawn ever anew. He often portrays his sitters with an unapproachable, hooded expression, sometimes lowered. He lent his Spanish Woman (see Gallery) that dark, enigmatic look, so typical of him, the unrevealing eyes which await one from behind the visor of the face. The very beautiful portraits of Giuseppina from the late 1930s have this quality of looking without revealing themselves.

-

Giuseppina with blue amphora, 1939

Oil on canvas, 70 x 50 cm

There are, to be sure, also portraits, which attract by confronting us openly and directly. A particularly beautiful example of this is the triple portrait of Vasco, Germaine and Felice: the two youths turn away from us, while the young red-haired woman in the middle steadfastly meets us in the eye with an attractive blend of earnestness and merriment. Derna Macchiaro belongs here too, as does the pastel portrait of Roboamo Poli (Gallery), whose clean-cut Tuscan head of a bird of prey holds one with ice-blue eyes. No less striking is Hippy at a table, thanks to the determined look in the eyes and the manner of the brushwork, as free as it is rich. Of similar quality in painterly execution is Paolo Pecile (Berlin, 2001). Staude had a particular penchant for the hippy generation of the ’60s and ’70s, in whom he found the chance, without borrowing from history, of linking a contemporary subculture (i capelloni – the longhairs) with Renaissance man.

-

Vasco, Germaine and Felice, 1952

Oil on canvas, 74 x 74 cm

-

Derna Macchioro, 1952

Oil on cardboard, 64 x 49 cm

-

Hippy at a table, 1970

Acrylic on paper, 46 x 34 cm

These are not the only instances of Staude’s playing with forms from the past in their contemporary manifestation. For instance, the pastel of a fair-haired Standing boy, in his shorts (Gallery), recalls Pompeian wall-paintings in its colouring and the organization of the background, also Renaissance portraits. And the Little girl in red (Berlin 2001, Table 60) looks out over a parapet in the manner of an early Renaissance half-length, though without the self-confidence we see in fifteenth-century sitters – indeed she is bashful rather.

Again in Staude’s free figure paintings we observe his dialogue with tradition. In an early composition, Venus in the Woods (Gallery), there are echoes of the Venetians and Hans von Marées. This picture attacks the classical theme of the Arcadian landscape, to which he will return in his figure scenes in Le Cascine, the Florentine municipal park, though in a way that is less tradition-bound. Boy at a table with eggs (Venice 2015) is reminiscent of Velazquez’ Bodegones, while Reclining Nude (1933, see Gallery)) employs the colour scheme of Corot’s small painting in the Petit Palais. On the other hand the figure painting Young People at Piazza di Porta Romana (1929) is a variation on the frescoes by Masaccio in Santa Maria del Carmine.

-

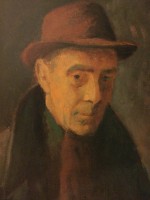

Self-portrait with hat, 1963

Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti

Oil on wood, 48 x 40 cm

Finally in this context we must turn to Staude’s self-portraits. These must count among the most attractive of their kind from the previous century. They impress by virtue of their sheer painterliness, their truthfulness and the complete lack of self-stylization. The late Self-portrait with easel (see Gallery), an important painting from the year 1968, shows him emaciated, isolated, in shades of bilious green and blue. In front of him are the objects that point to the activity of a lifetime – an easel and canvas.

VII. Cityscapes

To capture a city’s character in a painting requires patience, an intimate familiarity and a sharp eye for light, colour and the language of forms. Staude’s renderings of Florence and Rome, especially their suburban streets, and his scenes of Venice are quite unique in twentieth-century art. Kokoschka’s large cityscapes, those grand panoramas, baroque in their expansiveness, bird’s-eye views rather than the perspective of pedestrian or inhabitant, pursue totally different intentions. In Staude there are affinities with the urban scenes of the impressionists, and of Marquet and Utrillo, though his sense of form is very different [7].

Monet, Pissarro and others who painted the new Paris, the Paris of the newly-built boulevards, did more than giving us a mere rendering of the city’s aspect. It is actually as if these painters were the first to give Paris her face. They make us aware of her silvery light, the grey-blue of the zinc roofs, the green of the trees in Summer, the blonde or whitish gleam of the façades, the boulevards with their teeming crowds. Even today we still see Paris through these painters’ eyes. There is also a pastel by Staude, which gives a new, fresh look to that favourite subject, Notre-Dame de Paris, so that it unexpectedly recalls New York and the neo-gothic of the Woolworth Building.

-

Notre-Dame de Paris, 1961

Pastel on paper, 49 x 64 cm

The face of Florence on the other hand has her own centuries-old resolute composure, her own monumentality. So often she leaves painters without a chance. The art of a Canaletto could hardly convey this city’s aura. The architectural backdrops in quattrocento paintings come closest to its essence: architecture of almost monastic baldness and austerity. But what we have there is simply scene-paintings, in which the Florentine artists delivered their tales. Later attempts at cityscapes and street scenes lack the stamp of the impressionists in their portraits of Paris.

It was left mostly to Staude to discover and develop images of Florence, which matched her very essence, and indeed his feeling for closed forms, together with his highly developed sense of colour and light brought him within reach of it. It almost seems as if he were the very first to unveil her face, which has meantime been disfigured by tourism and traffic. Whereas plenty of representations of Florence (even Corot’s, which focus on the Duomo) strike us as translating her light and shapes into a dialect that is alien to her nature, Staude’s paintings seem formed from the material, the dust and the hues of the city herself and to speak her mother tongue. It is a discreet, reserved and luminous language, the language of silent walls, whose severity is softened by the foliage that peeps out from them. The walls, quiet streets and uncommunicative house fronts are not, however, the real protagonist. At least, they are not the sole one: it is rather the light, the cool morning light, the blinding midday and afternoon light, the waning Autumn light, that plays the leading part here.

Nevertheless, the world which is here described is not one in which man is unimportant. Although Staude avoids all anecdotal additions, or excursions into the picturesque, man is not absent from his paintings. Unlike Cézanne’s unpopulated landscapes, Staude’s street scenes are enlivened occasionally by small, isolated figures, who are there to tell us that the tranquillity, the silence, has nothing absolute about it, that it is the silence of the still-empty, or, at noon, again- empty street, which has the magic of the not-yet-trodden and morning-fresh, or else of the abandoned and deserted.

Staude coaxed from the earth-hues of Florence and her walls an undreamt-of colourfulness (Gallery, Berlin 2001, Plates 14-20, 22-24, 27, 40-44). The earth-hues, clay-hues of the city are the neutral substratum on which the light can work its entire magic. Southern cities, southern light, enable us to discover the colours of the achromatic: the dull brown of a wall, with the appropriate light on it, can become a whole spectrum of colours – glowing rust-red, ochre, orange, pink, violet, deep shaded blue. All this can spring from the colours of common day, in the play of light and backlight, of glow and reflected glow. It is not just a matter of illumination but of a light that emanates from the walls themselves, which seem to turn into a luminous colour substance, and to spread an atmosphere of colour around them. The art of pastel, as handled by Staude, is related to these phenomena in a very special way.

-

The Arno near Porta San Niccolò, 1945

Oil on wood, 25 x 31 cm

-

Casa Venturini, 1945

Oil on wood, 35 x 45 cm

-

Before the house , 1946

Oil on wood, 38 x 55 cm

-

Viale Petrarca and Giardino Torrigiani, 1955

Oil on cardboard, 48 x 65 cm

Staude did not entirely turn his back on monumental Florence and her famous sights, the dome of the cathedral, the Palazzo della Signoria; but in his later work they receded more and more into the background. In A view of Florence from the year 1968 the foreground contains a repoussoir of cypresses that seem to move of their own accord, behind which floats the Florence of domes and towers like a mirage, like a transparency. At the end of an ascendant curve of facades that juts from the Monte Oliveto appear the cathedral dome and campanile, seemingly perched on a hill, high above the rest of the city. Also characteristic is the view of Florence and the tower of the Signoria, The trestle bridge (Venice 2015) In the foreground are the river Arno and a makeshift iron bridge. The classic profile of the city, greatly simplified, is combined with this delicate example of modern construction. A pastel of the Church of Ognissanti (Berlin 2001, p. 30), again on the Arno, is almost darkened by the heat of the late afternoon sun. The bedrock of deepest silence has been reached. It is as if all individuality, every detail of colour and form were submerged in the stillness of things.

-

A view of Florence, 1967

Öl auf Leinwand, 50 x 70 cm

Staude’s art of painting hovers, as we have seen, on the borderline between the solidity of the concrete on the one hand, and, on the other, colour as an autonomous apparition. Of outstanding purity and beauty are the pictures of Florentine streets and squares from the ‘forties and ‘fifties. Staude, who knew the difficulties of oil paint, felt himself impelled towards exceptional firmness and subtlety, to a meeting of patience, resolution and presence of mind, to which the high level of these works is indebted. It is easy to find echoes of French impressionism in these paintings. The Foundry of the Pitti collection, for example, is reminiscent of Pissarro at his finest. And yet Staude avoids eclectic borrowings from impressionist technique: he develops his handling of colour and brush in debate with the subject. His superb conception of form is linked to a sense of colour tones, gradations and transitions, which save him from the restless fragmentation of later impressionist production.

-

The Foundry, 1946

Oil on wood, 42 x 57 cm

Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Palazzo Pitti

Staude’s favourite subjects during the post-war years came from his immediate vicinity, the streets and squares around the hill of Bellosguardo and the area around the Porta Romana. Here at will he could study the logic of colours and forms, of silence and light, and of the times of day. Here this logic could emerge with exceptional purity, free from all the ingredients of the picturesque, the literary, or the touristic. The melancholy restraint of some of these paintings, which are often on the small side (Via di Marignolle, see Gallery) or Via de’ Serragli, with their harsh poetry, may in some respects bring the post-war neo-realist cinema to mind.

-

Via de’ Serragli, 1947

Oil on wood, 60 x 45 cm

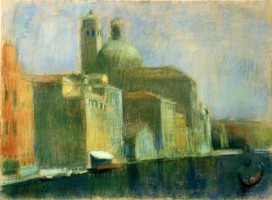

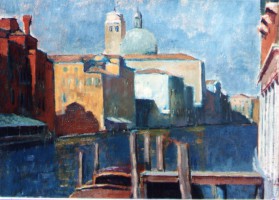

In his early paintings of Venice we also occasionally discover an ashen tone, a holding back that is a far cry from the expected. Even in his most luminous portraits of the city, however, particularly when using pastels, Staude frees the famous city from its picturesque flair. His feeling for large forms, which was schooled in Florence, reveals Venice’s splendid and monumental traits. Whereas in Turner and Monet the evocations of the city are focussed on the atmospheric and the momentary: water, haze and clouds, in Staude Venice emerges as architecture, yet architecture constructed out of coloured light, out of coloured light-bodies, if one may say so. His pastels of the church of San Geremia take their cue from Monet in depicting one and the same subject by different lights of day. But he eschews Monet’s fracturing of form into tiny particles: this not infrequently works against the luminous effect of colour. And Turner seems to suspect the city rather than seeing it. Instead Staude reinforces the cubist massing of the architectural ensembles, and this adds to the interest of colour and light in unsuspected ways. The areas of shade are transformed into colour zones before the painter’s patient eye; indeed they reveal a hidden glow, which transforms Venice into a city of oriental magic. This impression, incidentally, is achieved by means that owe nothing to picturesque or literary additions.

-

San Geremia in the morning III, 1958

Pastel on paper, 50 x 70 cm

-

San Geremia in the afternoon II, 1964

Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

Rome, particularly her modern suburbs that combine the rural and the modern, and, again and again, modern Rome to which Staude lends a pinch of North Africa, were an inspiration to the painter before the traffic made painting there impossible.

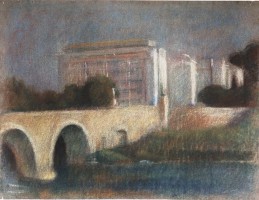

-

Ponte Milvio and Via Cassia, 1955

Pastel on paper, 45 x 60 cm

-

Via Cassia, 1958

Oil on cardboard, 47 x 67 cm

-

The new Rome with palmtrees, 1955

Pastel on paper, 45 x 60 cm

A picture with an almost classical air is Roman street in the evening light. This scene with heavy masses of shadow from the wall and cypresses on the left, its purple and violet, its turquoise-green shadows on the salmon-pink house, its almost deserted street, convey a Roman feeling for life that has almost gone lost today.

-

Roman street in the evening light,1959

Oil on canvas, 57 x 65 cm

-

Santa Maria dei Miracoli, 1955

Pastel on paper, 48 x 62 cm

-

Villa Medici, 1955

Pastel on paper, 48 x 63 cm

The Rome of the great monuments captivated Staude just as much as the modern blocks of flats that approached his ideal of cubist simplification. We see before us a painting of the gleaming façade of Saint Peter’s, the fountain, a section of Bernini’s colonnade, as if concertina-ed by a telephoto lens (see Gallery). Or Piazza Navona by Twilight (Berlin 2001, p. 33) as a shadowy and ghostly complex of forms, Villa Borghese, Trinità dei Monti (Gallery), Santa Maria dei Miracoli, or Villa Medici.

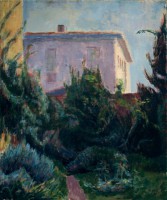

VIII. The Garden. Castagno d’Andrea

With regard to Staude’s last paintings, people have spoken of his ‘green period’. In studying the succession of subjects in his work, one traces a line of withdrawal – a withdrawal from the centres of cities to their suburbs and to Le Cascine, from the suburbs to the calm of his garden and the Apennines. Cities begin to disappear, not least because it was becoming more and more impossible to set up an easel in crowded streets. So it is, that Staude’s cityscapes, for all their quality as art, also have a documentary importance: they conserve an image of Florence, Venice and Rome that is under treat. Despite all the wonderful potential of film and photograph, it is only painting, so often pronounced dead, that can provide the special feel of physical contact with things, whereby the spirit that reigned in the city of yore can still be savoured.

Staude, rather like Monet, withdrew from the city to within the enclosure of his garden, which, from scant beginnings he transformed into a fertile, colourful chaos. It appears larger and more impressive in his paintings than it was in reality. His bilious green, his blooms and his probing of the gloom are reminiscent of Klingsor’s magic garden in Parsifal (whereas his pastels, with their unconfined tones, remind one mainly of Debussy’s ‘musical paintings’.) His flower pieces provide further witness to the love of his garden (see Gallery).

-

The white house beyond the garden, 1970

Acrylic on canvas, 71 x 50 cm Akryl auf Leinwand, 71 x 50 cm

-

The studio’s garden, 1971

Acrylic on cardboard

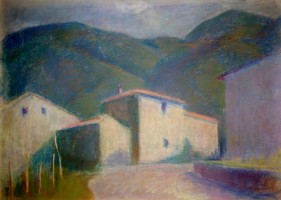

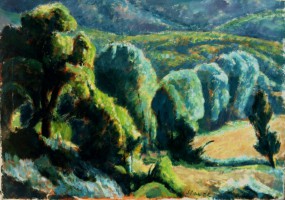

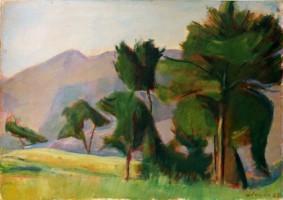

Castagno d’Andrea, the birthplace of the fifteenth-century painter Andrea del Castagno in the Tuscan Apennines, provided the impulse for Staude’s last important series of paintings. The village of Castagno with its bright-red roof-tiles was a trove, a culmination of that double quest of his, cubist simplification and luminous colours. In his open landscapes, however, a new feeling for form prevails. The ‘great form’, to which Staude dedicated his life, now begins to take on a life of its own. The trees fuse into zoomorphic clusters, sculptural shapes, but without congealing into fixedness. Rather they are on the point of transmuting themselves and adopting fresh forms. In the painting of the Apennines there reigns an urge towards constant metamorphosis, towards ever new ‘Gestaltung und Umgestaltung’, arrangement and rearrangement, which the artist himself felt to be novel in kind, no less than his occasionally bilious colouring [8].

-

Le Prata, 1967

Pastel on paper, 50 x 70 cm

-

Bird’s eye view, 1970

Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

-

Trees and mountains, 1967

Acrylic on canvas, 50 x 70 cm

In connection with his Castagno landscapes, he was particularly happy to meet a ‘man of the people’, probably one of the numerous artisans one used to come across in Florence, whose keen powers of observation and striking use of language were enormously appreciated by Staude. When this man found himself in front of one of the few large Castagno landscapes, the thought that occurred to him was of the rhythm of the world at the moment when it came into being, a rhythm that stretched from the sky and the rocky massif in the background down to the wooded hills and clumps of trees in the foreground. What strikes one most about some of the Castagno pastels is how, using Nature as a model, Staude achieves a strange irreality. Nature here seems remarkably unsubstantial, dematerialized. Its impulse comes from within. Dipped in feverishly bright colours – purple, mauve, brilliant green and yellow-green – it approaches dissolution. This series of paintings was Staude’s last great achievement. Maybe constant exposure to the dust of his beloved pastels brought on the illness to which he finally succumbed.

IX. Conclusion

Time and again Straude excercised himself over the question of his own modernity. It either amused or worried him. Was he up-to-date? Was he passé? Especially in the post-war years he found himself progressively isolated from the art world. He was to know admiration and acclaim from several Italian painters of his generation, and from younger people too, though these for the most part did not belong, strictly speaking, to the world of the fine arts. To a marked degree he became friendly with the philosopher Giorgio Colli and the composer Luigi Dallapiccola, both of whom, like the pianist Géza Anda, were able, with their spiritual kinship, to appreciate Staude’s art, both its discretion and its radiance. All of them owned works by him.

As for what constitutes modernity, we are nowadays better placed to recognize its pluralism and absence of simultaneity. Nor does this apply only to postmodernism [9]. Meanwhile there should be no contending that modern art (which does not coincide with that of the twentieth century) cannot be pinned down entirely to the schema devised by Theodor Adorno, Gilles Deleuze and the American art critic Clement Greenberg. (Arthur Danto deserves a mention here, too.) This propounds a more or less linear progression that stretches from cubism to Rothko and Barnett Newman. Great though the value of these critics and philosophers may be for the understanding of the modern art movement, let it also be said that they have opened the gates on an oversimplified notion of modern art history. The lack of contemporaneity in things that are related, and the contemporaneity of those that are not, could hereby be obscured. While Morandi was painting his small, exquisite, dust-coloured still lifes, non-figurative painting attained one of its peaks in the work of Pollock, Rothko and Gorky. Thus it is that the twentieth century knew a juxtaposition of such artists as Schwitters, Beckmann, Bonnard and Edward Hopper, all as different as they are important. We find the figurative side-by-side with the non-figurative, art concrète with an old-masterly style of painting. This scarcely constitutes linear development. Adorno was already conscious of the disparity, and of the loss, too, that artistic ‘progress’ entails. Hence his championship of forgotten modern and early modern composers. Staude himself is one of the forgotten. His style, though never idyllic, was lyrical, far removed from the tendency of many an important painter towards the extreme, to a clear break with tradition.

Wherein lies his modernity, then? First, without doubt in the loneliness with which he pursues his project, which arose from the study of his great ancestors and the tradition. Also in the emancipation of colour, which he pushed ever further, and in his unique combination of chromatic luminosity and a generous understanding of plastic form. Finally it is the silence that increasingly prevails in his pictures, that stamps them with the seal of modernity. H.-G. Gadamer, Theodor W. Adorno, Arnold Gehlen and others have pointed out how modern art tends towards silence. This can take on various forms, not only the silence of the breakdown in communication, but also a craving to re-establish the primal silence of Nature, of creation. Both kinds of silence, to differing degrees, are present in Staude. To restore to the world its primal silence was one of his paramount aims. What lends his work its special magic is his love of the colourful appearance, his yearning, as Nietzsche put it, for the “happiness of the eye to which the sea of existence has become calm, and which cannot see enough of this many-coloured, tender, trembling sea-skin.” [10], [11]

Notes

Pitti 1996, Berlin 2001, and Venice 2015 refer to the catalogues of the exhibitions in Palazzo Pitti, Florence 1996, the Spandauer Zitadelle, Berlin 2001 and in the Fondazione Cini, Venice 2015 (see Bibliography); ‚Gallery’ refers to the section of this name in this website.

Thomas Baumeister has teached history of modern philosophy at the University of Nijmegen.

This essay first appeared in the Catalogue “Hans-Joachim Staude. Paintings and pastels” of the exhibition “Hans-Joachim Staude. Poet des südlichen Lichts” in the Spandauer Zitadelle, Berlin, 4. Mai – 29. June 2001.

Translated by Nigel Foxell.